Latest Observation

2021.03.31 Wed

Observation for the stranded ship and vessel congestion in the Suez Canal

The grounding accident of the huge container ship occurred at around 07:40 (local time/05:40 UTC) on March 23, 2021 in the Suez Canal and vessel congestion had been continued. The stranded ship has successfully refloated in the evening of March 29 (local time), then the passage has reopened. 422 vessels were waiting for their navigation for a while, but according to the news reports on April 4, all of them have passed through the canal on April 3. However, many vessels newly arrived at the entrance of the canal, so it seems to take some time to fully clear the congestion.

JAXA observed the Suez Canal by Advanced Land Observing Satellite-2 “DAICHI-2” (ALOS-2) on March 26, March 31, April 6 and April 9 then confirmed the situation of the stranded ship and vessel congestion. There are reports of a sandstorm on the accident day. We will also introduce the observation of aerosol (dust) by Global Change Observation Mission – Climate “SHIKISAI” (GCOM-C).

Radar observation image by “DAICHI-2” (ALOS-2)

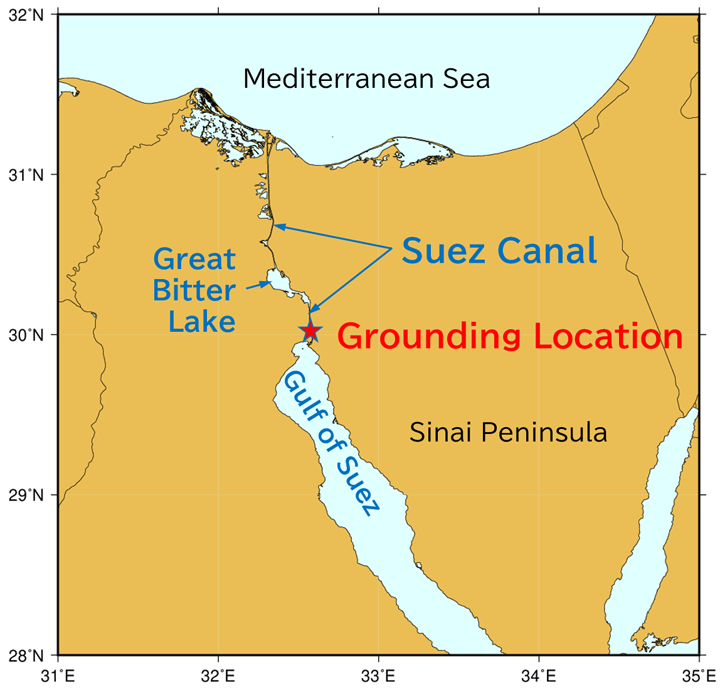

Figure 1 shows the map around the Suez Canal. The grounding accident happened at south side channel of the Great Bitter Lake, which locates in the midstream of the Suez Canal.

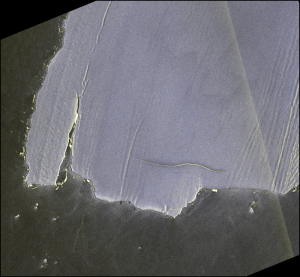

Figure 2 shows the image around the stranded container ship observed by PALSAR-2, synthetic aperture radar onboard ALOS-2, at 10:23 (UTC) on March 26. The ship is the 400m-long in total, longer than the width of the canal. As seen from the figure, it’s completely blocking the canal. We can find ships like tugboats etc. around the stranded ship.

Figure 2. Image observed by PALSAR-2, synthetic aperture radar onboard ALOS-2, at 10:23 (UTC) on March 26. a) around the Suez Canal b) extended image around the stranded ship

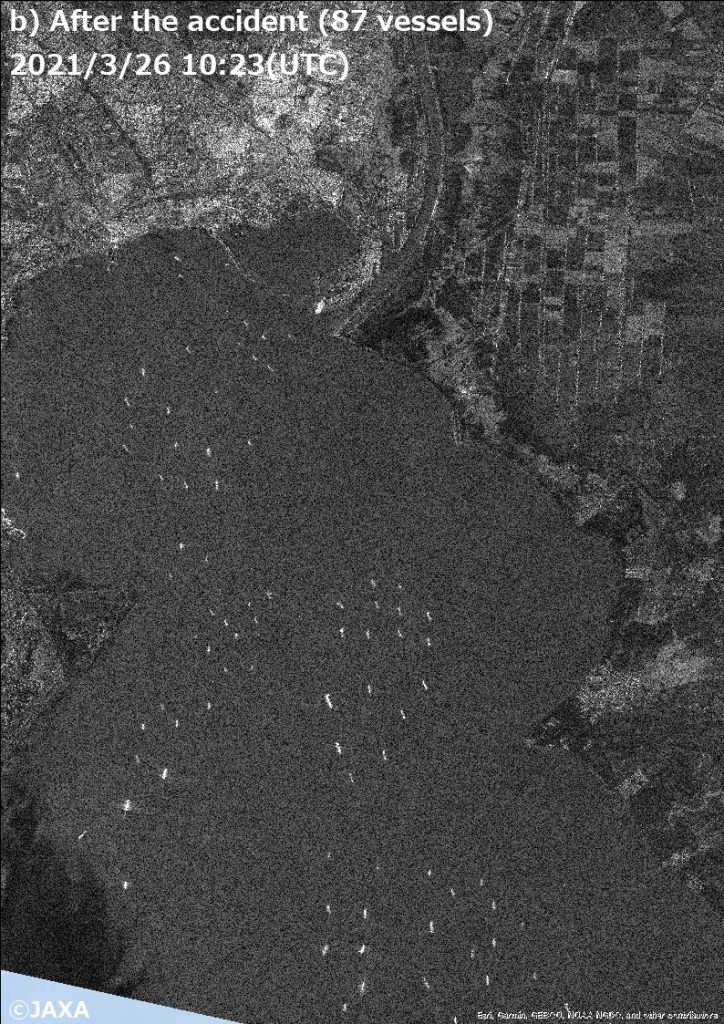

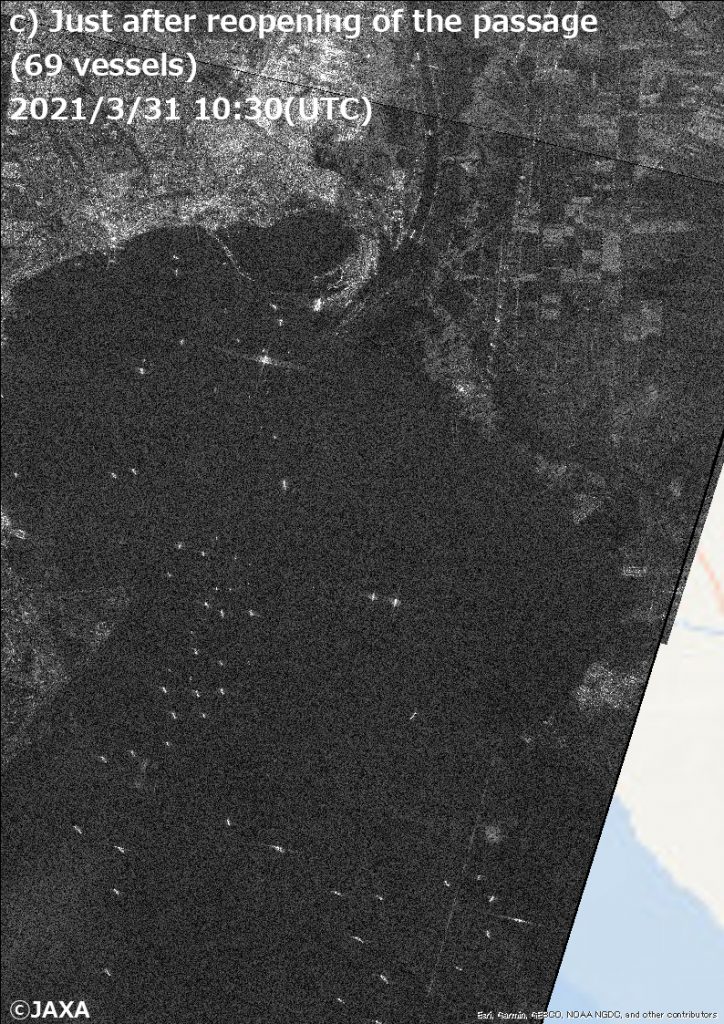

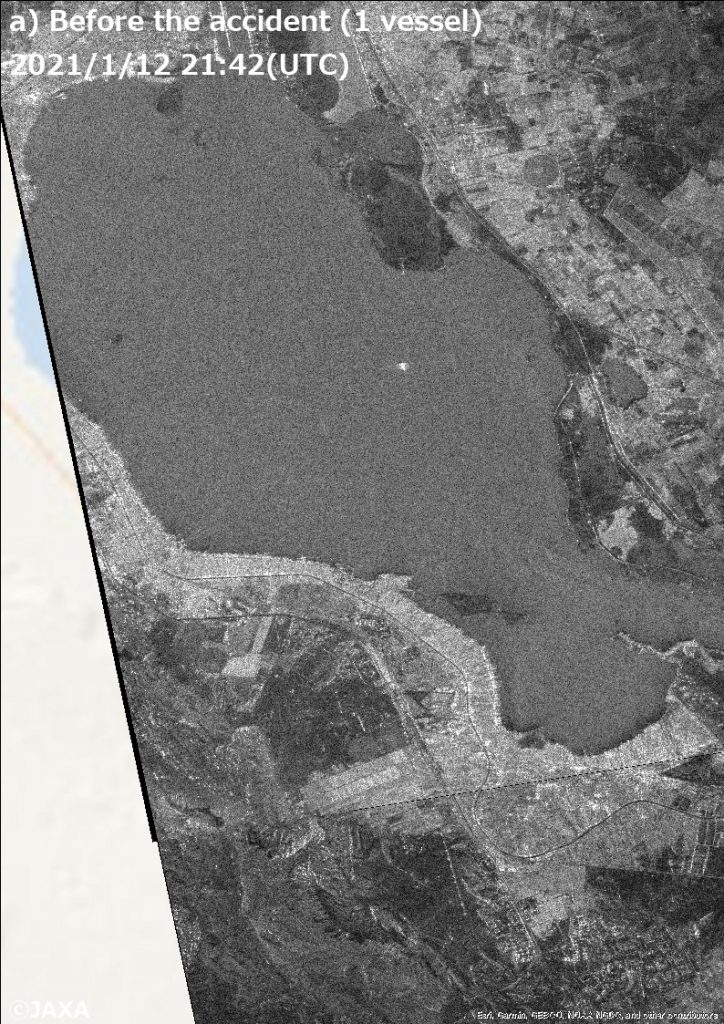

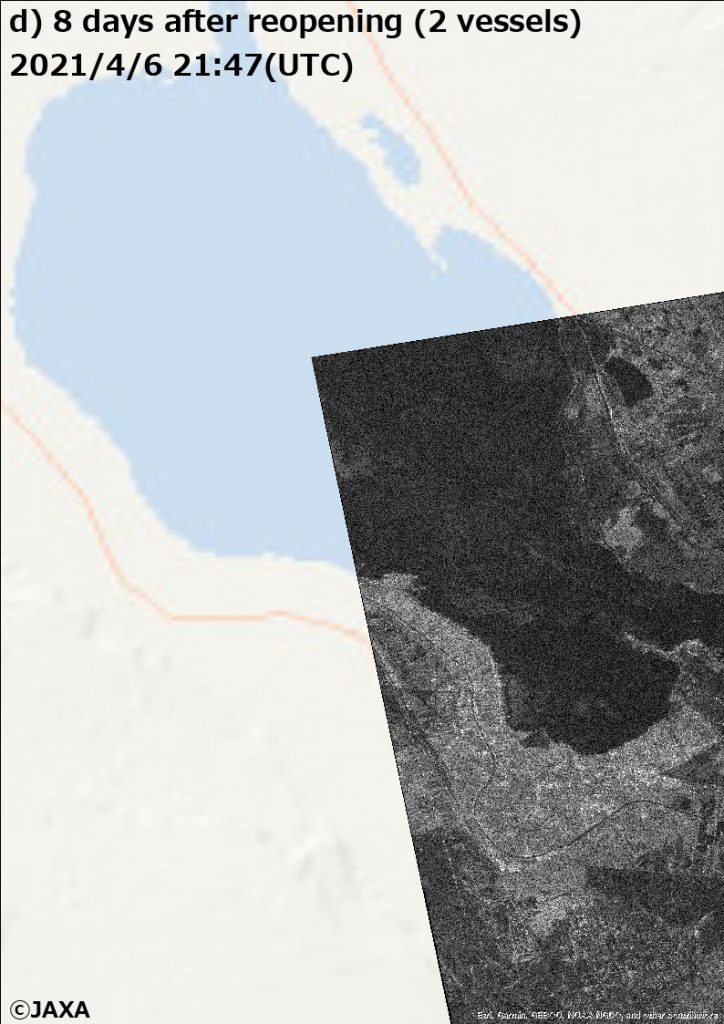

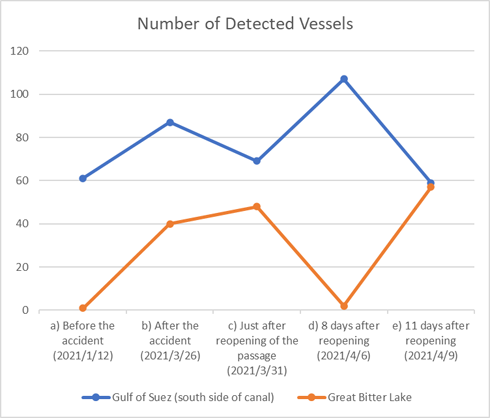

Figures 3 and 4 show the radar images from January 12, before the grounding accident to April 9, after recovery of normal passage. Fig. 3 covers around south side entrance of the Suez Canal (the Gulf of Suez) and Fig. 4 covers around the Great Bitter Lake located north side. Each bright spot over the water shows vessel. Figure 5 is a graph showing the change of vessels’ number in the Gulf of Suez and the Great Bitter Lake (We counted the number only in the captured parts for both cases).

As for the side of the Gulf of Suez, the condition can be found that vessels are always standby for the passage regardless of the accident (Fig. 3). Vessels staying in the Gulf of Suez were confirmed (61 vessels) on January 12, 2021, before the accident but the number increased to 87 on March 26, after the accident. The number decreased to 69 on March 31, after restart of the passage. When the passage normalized, there were 107 vessels on April 6, and 57 vessels on April 9. These conditions indicate that vessels are always waiting for the passage in the Gulf of Suez, regardless of the accident.

On the other hand, as for the case of the Great Bitter Lake, roughly two lines of vessels can be found in radar image after the accident (Fig. 4b). Moreover, there are vessels even between the lines on March 31 and April 9, after starting the passage (Fig. 4c, Fig. 4e). Especially, we can find ship tracks clearly in the image on April 9, indicating vessels are moving in the lake. The Great Bitter Lake is located on the midway of the Suez Canal and its north side is a single-track zone. In case this zone takes northbound passage (from the Suez Canal to the Great Bitter Lake), we suppose vessels entering the lake from the Mediterranean side are anchored in two lines, waiting for the passage from another side, while ships coming through the canal from the south are moving between the lines. Since no vessels passed between the two lines of vessels immediately after the accident (Fig. 4b), the number of vessels on Great Bitter Lake after the start of passage (48 vessels: March 31, 57 vessels: April 9) increased compared to the timing immediately after the accident (40 vessels). This kind of passage depends on the direction of passage of the single-track zone, so when the zone takes southbound passage, there will be no vessels in reverse. Therefore, as shown in Figs. 4a and 4d, we suppose that there are no vessels in the lake at different time (around 21:45 UTC). This time, the change of vessels’ number was examined by radar, but we will plan to conduct further way because the passage condition of each time slot is also needed to be considered.

<South side entrance (Gulf of Suez)>

Figure 3. Radar images around south side entrance (the Gulf of Suez) of the Suez Canal at a) 21:42 on January 12 (UTC) (before the accident), b) 10:23 on March 26 (UTC) (after the accident), c) 10:30 on March 31 (UTC) (just after reopening of the passage), d) 21:47 on April 6 (8 days after reopening) and e) 10:23 on April 9 (11 days after reopening)

<Midway of the canal (Great Bittler Lake)>

Figure 4. Radar images around the Great Bitter Lake (Midway of the canal, north side of the accident spot). Date and time are same as Fig. 3.

Figure 5. The change of vessel’ number around the Gulf of Suez and the Great Bitter Lake (We counted the vessels in the area shown in Figs. 3 and 4, but the number counted around the Great Bitter Lake on April 6 is a reference value due to the lack of observational region.)

Addition: ALOS-2 is possible to receive AIS signal, but it is difficult for satellites to receive AIS signal in case of ocean area where many vessels are existing. In areas close to land, like the Suez Canal, information of AIS received signal from antennas installed on land is utilized. Regarding the information of vessel location used AIS data on land, for example, live map of marine traffic is available).

Aerosol (dust) information observed by “SHIKISAI” (GCOM-C)

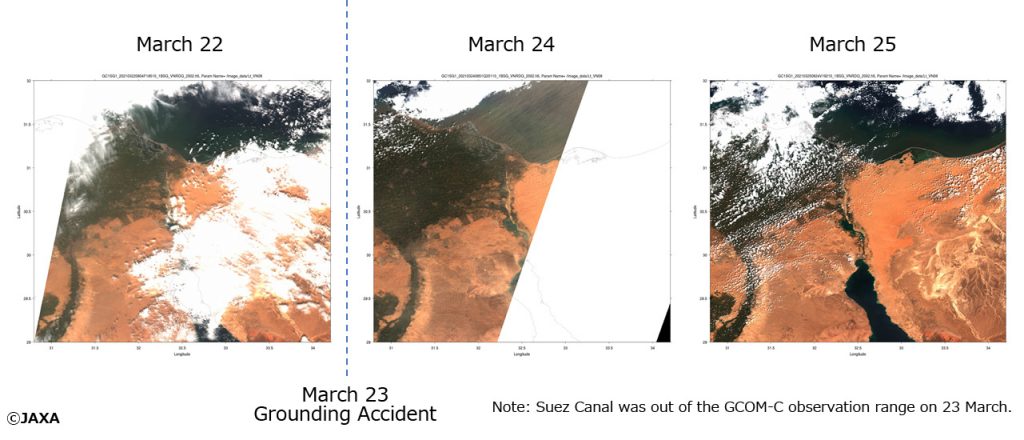

As for the cause of the accident, the effect of sandstorm is also reported. Figure 6 shows the observation result of aerosol by GCOM-C. The observation around the Suez Canal was out-of-range on the date of the accident, March 23, but GCOM-C observed many aerosols (dusts) on the next day, March 24 (Aerosols can be found as brown linear from southeast to northwest direction) .

Left: Extended figure on March 22

Middle: Extended figure on March 24

Right: Extended figure on March25

Explanation of the Images

Figures 2 and 3

| Satellite | Advanced Land Observing Satellite-2 “DAICHI-2” (ALOS-2) |

|---|---|

| Sensor | Phased Array type L-band Synthetic Aperture Radar-2 (PALSAR-2) |

| Date | Before the accident: January 12, 2021 21:42 (UTC) After the accident: March 26, 2021 10:23 (UTC) Just after reopening of the passage: March 31, 2021 10:30 (UTC) 8 days after reopening: April 6, 2021 21:47 (UTC) 11 days after reopening: April 9, 2021 10:23 (UTC) |

| Observation mode | Before the accident: SM3, ascending, right side observation, Off nadir angle: 32.5, polarized wave: HH After the accident: SM1, descending, left side observation, Off nadir angle: 28.7, polarized wave: HH Just after reopening of the passage: SM1, descending, left side observation, Off nadir angle: 38.2, polarized wave: HH 8 days after reopening: SM1, descending, right side observation, Off nadir angle: 32.9, polarized wave: HH 11 days after reopening: SM1, descending, left side observation, Off nadir angle: 28.7, polarized wave: HH |

Figure 4

| Satellite | Global Change Observation Mission – Climate “SHIKISAI” (GCOM-C) |

|---|---|

| Sensor | Second generation GLobal Imager (SGLI) |

| Date | March 22, 2021 (left) March 24, 2021 (middle) March 25, 2021 (right) |

Related Sites

・Seen from Space The Suez Canal: A shortcut for ships through the desert

Search by Year

Search by Categories

Tags

-

#Earthquake

-

#Land

-

#Satellite Data

-

#Aerosol

-

#Public Health

-

#GCOM-C

-

#Sea

-

#Atmosphere

-

#Ice

-

#Today's Earth

-

#Flood

-

#Water Cycle

-

#AW3D

-

#G-Portal

-

#EarthCARE

-

#Volcano

-

#Agriculture

-

#Himawari

-

#GHG

-

#GPM

-

#GOSAT

-

#Simulation

-

#GCOM-W

-

#Drought

-

#Fire

-

#Forest

-

#Cooperation

-

#Precipitation

-

#Typhoon

-

#DPR

-

#NEXRA

-

#ALOS

-

#GSMaP

-

#Climate Change

-

#Carbon Cycle

-

#API

-

#Humanities Sociology

-

#AMSR

-

#Land Use Land Cover

-

#Environmental issues

-

#Quick Report

-

#GOSAT-GW

Related Resources

Latest Observation Related Articles

-

Latest Observation 2025.12.03 Wed [Quick Report] Analysis results from satellite precipitation data on the record-breaking heavy rainfall occurring in Southeast Asia in late November 2025

Latest Observation 2025.12.03 Wed [Quick Report] Analysis results from satellite precipitation data on the record-breaking heavy rainfall occurring in Southeast Asia in late November 2025 -

Latest Observation 2025.10.01 Wed [Quick Report] Hurricane Humberto “Eye” captured by EarthCARE satellite (Hakuryu)

Latest Observation 2025.10.01 Wed [Quick Report] Hurricane Humberto “Eye” captured by EarthCARE satellite (Hakuryu) -

Latest Observation 2025.02.28 Fri The world’s largest iceberg, A23a, may have run aground on the continental shelf of South Georgia:

Latest Observation 2025.02.28 Fri The world’s largest iceberg, A23a, may have run aground on the continental shelf of South Georgia:

The trajectory of iceberg A23a observed by “GCOM-W”, “ALOS-2” and “ALOS-4” -

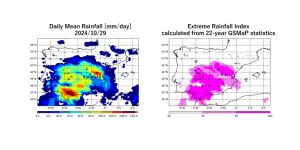

Latest Observation 2024.11.06 Wed [Quick Report] Heavy rainfalls in eastern Spain, as seen by the Global Satellite Mapping of Precipitation (GSMaP)

Latest Observation 2024.11.06 Wed [Quick Report] Heavy rainfalls in eastern Spain, as seen by the Global Satellite Mapping of Precipitation (GSMaP)